HISTORY

- 1885

- Founded “Ochaya Oumi-E” at Tominaga-cho, Yasaka-shinchi, Gion, Kyoto

- 1960

- Moved to Yasaka Street, Gion, Kyoto

- 1991

- Opened Japanese restaurant “Tempura Yasaka Endo”

- 2010

- Opened Japanese restaurant “Tempura Endo -South Branch-”

- 2012

- Opened “Ochaya Bar Oumi-E” in Miyagawa-cho, Gion, Kyoto

- 2014

- Opened “Kaiseki Yasaka Endo” in Miyagawa-cho, Gion, Kyoto

- 2015

- Opened Japanese restaurant “TEMPURA ENDO -Kyoto style-”

in Beverly Hills - 2016

- Opened Japanese restaurant “Tempura Endo -North Branch-”

- 2016

- Opened Japanese restaurant “Tempura Endo -West Branch-”

- 2017

- Opened Japanese cuisine “ENDO THE CELESTINE KYOTO GION”

- 2017

- Opened “Hotel Bar Oumi-E” in THE CELESTINE KYOTO GION

Tempura Symbolizes the Exchange of

Food Culture between Japanese and

European Stretching back some 500 Years

Tempura is now counted alongside Sushi as a representative Japanese cuisine.

But, did it actually originate in Japan?

There are several theories as to the origin of the word Tempura, all of which point to it being a derivative of the Spanish noun témpora or the Portugese noun tempero, indicating it arrived in Japan around the time of the Portuguese Jesuit missionaries when matchlock guns were firstintroduced.

A dish called tsukeage - sea bream covered with flour, deep fried in oil and served with seared chicken dressed

with thick starchy sauce - is believed to have been served in Kyoto during the late Muromachi period

when Tempura was still just a method of cooking and not yet a well-known cuisine.

It wasn't until the late Edo period that the name Tempura first appears in writing.

The tsukeage that spread in Kyoto during the Muromachi period rapidly gained popularity as Tempura in Edo. Rather than seam bream, the Tempura served in Edo was made from cheaper ingredients such as shrimp, shellfish, conger eel and gizzard shad. Tempura, like sushi, was mainly sold by street vendors in much the same way fast food is sold in America and other Western countries today.

Born of cultural exchange between East and West and a convergence of domestic culture spanning Japan's mainland, Tempura is indeed a symbol of the international exchange of food culture.

CD-ROM Version (Issued by Yumani Shobou)

Tempura is a Symbol of Food Culture

Exchange Loved by All Walks of Life

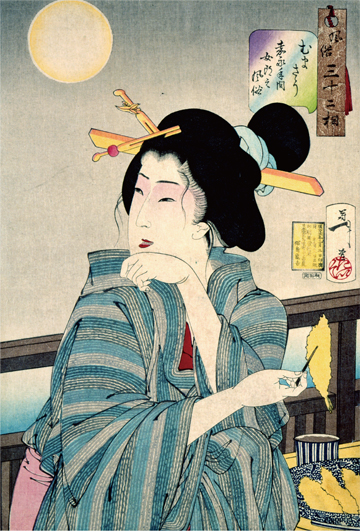

The colored woodblock print seen here was printed in the closing years of the Edo period. The woman can be seen about to enjoy a delicious serving of deep fried shrimp. Street vendors at the time would serve freshly fried Tempura that customers would eat using a skewer or chopsticks and dipping in Tempura sauce.

This was a popular everyday food that could be quickly and easily eaten with a single hand.

Deep fried foods like Tempura originally made their way from Kyoto and Osaka to Edo.

The fact that oil based cooking methods were widely adopted in Kyoto is deeply rooted in the large number of temples and shrines in the area. Come the second half of the 17th century, cotton and rapeseed were heavily harvested for lamps in temples and shrines, resulting in the significant advancement of oil compression and refining techniques. Oil prices dropped, giving common people access to oil for cooking. This was especially so in Kyoto where people would come from across the country to enjoy the likes of Kyo-yasai (Kyoto vegetables), tofu, tofu skin, and konjac tempura.

While Tempura was still a popular everyday food come the Meiji period, the street vendors were slowly replaced by restaurants, some of which began to serve high-class Tempura using special oil and cooking techniques.

Many cooks moved to Tokyo from the Kansai Region after the Great Kanto Earthquake, seeing the general popularization of Kansai style Tempura, an assortment of both fish and vegetables that is deep fried until golden and eaten with a sprinkle of salt.

Tempura has evolved into a representative Japanese cuisine that continues to be loved by all walks of life.

(Printed by Yoshitoshi Oso)”

(Owned by Ajinomoto Dietary Culture Center)